Exceptional writing in a young adult with Down syndrome

Until recently, there have been few studies of language development in the Down syndrome population. Within the past fifteen years, studies have been done concerning the writing abilities of people with Down syndrome. None of these studies, however, have focused on a high functioning person with Down syndrome. This study demonstrates the ability of someone with Down syndrome to make incredible language achievements. I used my sister, Rose, as the subject of my study. Rose was born five years before me; at birth she was diagnosed with Down syndrome. I analyzed 62 of Rose's journal entries, dating from 1998 to 2005. From these journals, I was able to see the language accomplishments that she has made. These include metalinguistic awareness, correct sentence structure, correct use of parallelism, correct use of temporal phrases, correct use of conditional phrases, and an interesting narrative structure and writing persona. Rose has achieved incredible language accomplishments. This is due in part to the early intervention program she completed, as well as her home atmosphere. There, she was given intensive treatment, and she was treated as a capable person, not a disabled individual.

Down Syndrome Research and Practice

Until recently, there have been few studies of language development in the Down syndrome population. Within the past fifteen years, studies have been done concerning the writing abilities of people with Down syndrome. None of these studies, however, have focused on a high functioning person with Down syndrome. This study demonstrates the ability of someone with Down syndrome to make incredible language achievements. I used my sister, Rose, as the subject of my study. Rose was born five years before me; at birth she was diagnosed with Down syndrome. I analyzed 62 of Rose's journal entries, dating from 1998 to 2005. From these journals, I was able to see the language accomplishments that she has made. These include metalinguistic awareness, correct sentence structure, correct use of parallelism, correct use of temporal phrases, correct use of conditional phrases, and an interesting narrative structure and writing persona. Rose has achieved incredible language accomplishments. This is due in part to the early intervention program she completed, as well as her home atmosphere. There, she was given intensive treatment, and she was treated as a capable person, not a disabled individual.

Within the last two decades, better support for language and learning in children with Down syndrome has resulted in stronger abilities in this population as well as more careful documentation of their development. Yet, even now, learning is still assumed to plateau for this population at around the fifth grade, with a shift to the acquisition of life skills after this age [1] . Hence, there is little motivation at present to investigate the literacy achievement of adolescents and adults with Down syndrome. This is unfortunate, given findings that language learning in persons with Down syndrome can continue throughout late adolescence and young adulthood [2] . As Chapman and her associates point out in their research on language and cognition, earlier studies typically ignore the production of extended texts and hence fail to record the complex sentence structures that persons with Down syndrome are actually capable of constructing [2,3,4] .

Down syndrome research on language has generally paid more attention to deficits than to abilities. Much of the research has focused primarily on low-level skills in reading as well as narrow aspects such as phonological awareness and lexical development [5,6,7] . One notable exception is the work of Rondal and his associates, which documents the language and cognitive abilities of Françoise, a French-speaking woman in her thirties with standard trisomy 21 [8,9,10] . Rondal and Comblain [10] provide a detailed analysis of Françoise's exceptionally strong language ability, including her writing. Rondal also discusses the exceptional writing ability of another person with Down syndrome, Paul, who has an "IQ about 60" [8:p.23] . Rondal found few syntactic errors and the presence of both subordinate and coordinate clauses in Paul's diaries, written from age 11 to 43.

More detailed linguistic descriptions from case studies similar to those of Françoise and Paul would allow us to gain deeper insight into this important aspect of the life of high-functioning adults with Down syndrome. The present study thus reports on the language ability of an English-speaking person with Down syndrome, Rose, who has been writing regularly in her journals from 17 to her present age of 26. The present text analysis of Rose's writing goes beyond sentence structure to explore how her narrative structures provide insight on her cognitive functioning and ability. In doing so, the present study highlights certain issues concerning the teaching of persons with Down syndrome and raises the question as to what should constitute 'lifelong skills' for this population.

Methodology

Case study

Diagnosed with the trisomy 21 variant of Down syndrome at birth, Rose received special education early intervention in the United States since she was three months old before enrolling in a pre-school handicapped program. Formal evaluation at the age of three documented that while her "developmental milestones were delayed, skills appeared in the appropriate sequence" (Pre-School Classification Report/Education Plan). Rose was classified as "Educable Mentally Retarded" (EMR). Except for a one-year immersion in a regular pre-school program at age four, Rose was educated in a special needs class throughout her school years until her graduation from high school in 2002 at the age of 21. Rose continued to receive speech therapy up till graduation. Because she continued to demonstrate progress, Rose's education throughout her school years remained focused on academics, not just vocational skills alone.

Rose was taught writing at school from a young age, beginning with practicing basic strokes at age three. Rose was able to print her name by age five. Her writing ability at age six was documented as being at a "high kindergarten level" (Annual Review). Rose was mainstreamed for reading in the fourth and fifth grades. In the mainstreamed classroom, Rose was asked to write summaries and reader responses. Writing skills were reinforced in Rose's special education classroom and at home throughout middle and high school. Grammatical instruction was introduced during her late elementary and early middle school years. In high school, Rose began journal writing while taking a mainstreamed writing course for two years. Rose graduated from high school after completing a six-year program, which also included two years of training in clerical careers.

At home, her parents offered full support to Rose, an only child for the first five years of her life. Rose's mother, a certified elementary school teacher, became a stay-at-home mother to help her with her academics throughout her school years. Since graduation, Rose has been working as a secretarial assistant in the building department of a township in New Jersey. Her duties include filing paperwork, using the computer for data entry, answering calls, issuing permits and certificates, and helping residents with various queries.

Corpus

The present analysis of Rose's writing is based on a corpus of 66 journal entries (61 pages) which she wrote between the age of 17 while in high school to 24, three years after graduation. These journal entries were written neatly in cursive with few graphic, spelling, grammatical, or syntactic errors (see Errors section below). Most of the entries were written in complete sentences and followed the conventions of journal writing. Rose's entries covered a wide variety of topics, from family vacations, school, work to social life. At first, Rose kept her journal as part of her school curriculum, but soon it became a routine in her everyday life.

Text analysis

The following linguistic aspects were investigated:

- Errors in punctuation, spelling, grammar, word choice, and sentence structure. All errors were recorded, including accidental ones due to hasty writing. Possible causes for the errors as well as patterns of errors were noted.

- Lexicon, comprising function words and full lexical items. Word usage was checked for semantic (meaning) appropriateness. Syntactic correctness was determined by considering whether Rose followed the collocational restrictions of each word, e.g., throw a party not do a party . The variety of her vocabulary including use of uncommon words was also noted.

- Sentence length and structure. Types of clauses and their combination in sentences were documented. The presence of coordinating and subordinating conjunctions - indicating awareness of certain logical relations - and the absence of others were noted. Types of sentences were also linked to the communicative functions performed.

- Narrative structure. Two main aspects were examined: temporal organization and pronoun usage. The organization of full texts by temporal marking (e.g., tense, conjunctions, words such as today) was investigated. The order of the presentation of events in each entry was compared to the actual chronology of the same events to see how much control Rose had over narrative structure and how flexibly she could handle time in her reporting. Consistency in pronoun usage served as an indicator of Rose's ability to keep track of the actors in her narratives. Given the level of sophistication of Rose's writing, stylistic aspects such as writer's persona, voice, and rhetorical features were also considered.

- Modality, the speaker-writer's attitude towards the truthfulness of a proposition. Modality, as conveyed in such elements as modal verbs and adverbs, is an important measure of cognitive ability. Linguistic items conveying different degrees of truthfulness or certainty were investigated, including types of negation.

- Metalinguistic awareness. Following text analysis of the corpus, Rose was interviewed about her writing on seven occasions at home. Her responses in the interviews were used to determine the kinds of strategies used in her writing and avoidance behaviors concerning certain linguistic forms. Brief informal tests were occasionally given during these interviews to confirm her ability to use certain forms that were absent or used incorrectly in the journals. These sessions lasted between 15-45 minutes each and consisted of questions that prompted Rose to respond using specific terms or phrases.

Errors

Errors in the journal entries are denoted by asterisks (*) immediately preceding them. The dates in parentheses following the excerpts indicate when the journal entries were written. Blanks indicate that parts of the date were not recorded in the entry, e.g., 8/__/1998).

Nineteen of Rose's 66 journal entries were completely error free, save for a single minor mechanical error (see excerpt in Appendix A). The majority of the errors were due to minor punctuation mistakes and did not have any significant effect on the clarity of the text. The most frequent punctuation error, occurring 67 times, involved omission of a comma before a coordinated independent clause. The remaining eight comma mistakes involved lists and city/state divisions. Ten omissions of punctuation marks led to run-on sentences, e.g.,

I went to Pennsylvania for Labor Day Weekend * and guess what I did on Saturday and Sunday night * we all went boating on our lake. (8/22/1998)

There were 25 fragments in the corpus. The majority of these, however, may be attributed to stylistic choice. In these cases, punctuation was used to create a sense of excitement, as in the insertion of an exclamation mark in the middle of the sentence below:

I have bowling today. I can't wait! Because on Sunday we have another bowling party. (1/27/2000)

Rose used the semicolon once but not correctly:

By the way *; Did I tell you that I'm going out for lunch after bowling on Thursday with Stephen? (8/4/1998)

Despite the large number of lexical items used (see Lexicon section below), only 15 were misspelled. Two involved the word football, which was misspelled twice as * foot ball, indicating that the wrong form had been internalised. Some words were probably misspelled because Rose had not actually encountered them in print, e.g., * barague for barbeque (6/_/1998); * karokee for karaoke (6/21/2002). For less common words, misspellings seemed to be the result of mishearing, e.g, * balances for valances (1/26/2003). A number of Rose's spelling errors were caused by hasty writing (e.g., * Bey for Bye (8/4/1998)); the same words were spelled correctly in other entries. Two of Rose's spelling mistakes involved the incorrect use of homonyms, * there for they're (8/25/00), and * where for we're (6/_/1998). Rose self-corrected this same error in another journal entry:

While we where were watching we ate our ice cream. (7/16/1999)

Grammatical errors were also rare, occurring only three times. Two errors involved subject-verb agreement with plural subjects:

My sister and I *is getting our teeth cleaned. (8/4/1998)

Elsewhere in the corpus, subject-verb agreement involving plural subjects did not pose a problem. The other grammatical error involved the only instance of a misplaced modifier:

Later on, in the night we saw fireworks * sitting down on the dock. (7/4/2002)

Inappropriate word choice was also rare in the corpus. Most involved prepositions, e.g.,

He'll be surprised *of me of how well I bowl. (1/27/2000)

Stephanie also made him a CD. *On which, he loves. (7/18/2005)

Some function words were sometimes mistaken for similar-sounding words in certain contexts, e.g., 8 *in a half for eight and a half (8/4/1999); I had *a best time with Jesse (6/21/2002).

Most of Rose's sentences were well-formed (see Sentence structure). Occasional sentential errors seemed to be due to hasty writing unaccompanied by proofreading:

Everybody *and an awesome time! (6/30/2002)

We * also going to the farm market for some things… (6/_/1998)

Even though these were only diary entries for personal expression, Rose edited her writing in some cases. Occasionally striking off a word or a sentence, Rose even crossed off one entire entry and rewrote it - even though there were few errors in the deleted segment (see Appendix B).

Confused or tangled expressions were absent in Rose's writing. Called "language mazes" by Loban in his extensive study of elementary school children [11-12] , tangled expressions appear commonly in the speech of typical school children, e.g., "…my mother called me up in the house/ an' [an' an' have to] I have to get my hair combed" [9 , 11] . These forms are also frequently seen in remedial writing in college [13] . Mazes are important to consider here because they signal the lack of control over language production - and they are noticeably absent in Rose's writing. All of Rose's entries were neatly structured with a beginning, middle, and concluding statement. There was no abandonment of intent, and hence no disconnected fragments.

Lexicon

All major lexical categories were present in the corpus, including adjectives (refreshing [7/4/2002]) and adverbs (extremely [8/7/2005]). Rose purposely avoided using what her high school teacher called "garbage-can words," which included words such as got. In her interviews, Rose said that she preferred to use "more exciting words" such as especially, receive, and instead.

Rose's vocabulary was varied, reflecting her ability to acquire new words as she experienced a diversity of situations. There were references to popular culture such as music videos (7/2/2002); context-specific words as in docked a boat (7/30/2005) and surrey (4/9/2004); prefabricated patterns, e.g., hot and humid (7/4/2002) and getting a tan (8/9/2005); foreign words such as foccaccia bread (8/7/2005); and compounds such as precision team (1/20/2003) and toss pillow (1/27/2003). Work-related jargon began appearing in her journal when Rose started working, e.g., block numbers (8/7/2000), Temporary Certificate of Occupancy, and Certificate of Habitability (2/24/2004). Her words were usually appropriate to the situation, e.g., describing the Cherokee Indian Nation as historic (7/4/2001).

On rare occasions, a few words were used appropriately but misspelled, perhaps indicating a hearing problem (see Discussion below). For example, Rose misspelled gasket (in a motor) as casket (7/__/1998). Similar mistakes have been documented above in the Errors section.

Sentence structure

The entries for this eight-year period varied widely in length, ranging from one to 32 sentences per entry. The shortest sentence had only three words; the longest 28 words. The longest sentence after graduation was 18 words. Prior to that, Rose's sentences were often over 20 words. The number of words per entry dropped after graduation from an average of nine words to seven.

To analyze Rose's syntactic patterns, two entries from each year were randomly selected for review, yielding a sample of 16 passages. In this sample of 16 entries, 19 out of 20 parallel structures were produced correctly, with an inversion of parallelism executed successfully once:

[I just received the card back] and [everyone signed it.] (1/27/00)

We have our midterms this week. *[One in chorus] and [for me in Home Ec.] (1/24/00)

[Some of my girlfriends slept over], and [so did I.] (6/18/02)

The clauses [I just received…] and [everyone signed…] were coordinated properly. But in the second excerpt, the noun phrase [One in chorus] was incorrectly conjoined with the prepositional phrase [for me…]. Inversion [so did I] was produced correctly in the third excerpt.

Complex sentences in the corpus took a variety of forms. Several involved temporal relations, as in

I also get exercise while I'm skating. (1/20/2003)

Conditional sentences were also used correctly, e.g.,

If you said yes, *your right. (6/29/1999) (you're misspelled *your)

Not only did Rose use a variety of sentence types she sometimes combined subordination and coordination in the same sentence:

[I was fine] [until I got home] SUBORDINATION

[and read her love note.] (8/25/2005) COORDINATION

Or consider the well-balanced sentence below:

[We started [to head back]] [because it started [to thunder]]. (7/16/1999)

Complex predication is used in both parts of the sentence above (started [to head back] and started [to thunder]). Logical subordination with because is used to link the dependent clause to the main clause.

Even more sophisticated structures can be found in the corpus, as in:

[I love it] [when I am up in Maine] SUBORDINATION

[because I get to [go to some beaches] SUBORDINATION

and [go boating]]. (7/__/1998) COORDINATION

The sentence above contains two subordinate clauses ([when...] and [because...]) together with coordinated verb phrases ([go to some beaches] and [go boating]) and a complex verb phrase (get [to go]).

Not all of Rose's sentences were simple declarations of fact. Syntactic variety enabled her to fulfil a diversity of communicative functions. Interrogative sentences in her journal demonstrated rhetorical skill:

Did you know that I am working this summer? (6/29/1999)

Guess what I did with my family? (6/22/2002)

In spite of Rose's syntactic sophistication as illustrated above, there were nevertheless gaps and discrepancies that should be noted. Coordination far surpassed subordination, with coordinating conjunctions appearing 243 times in the corpus compared to 127 for subordinators. Tables 1 and 2 display all occurrences of coordinating and subordinating conjunctions in the whole corpus.

| Coordinating conjunction | Frequency |

| And | 214 |

| So | 19 |

| But | 8 |

| Or | 1 |

| For | 1 |

| Yet | 0 |

| Nor | 0 |

Table 1 | Use of coordinating conjunctions in corpus

Rose used coordinating conjunctions and, so, and but and subordinating conjunctions such as after, because, before, if, since, until, and while correctly throughout her writing. However, other coordinating conjunctions (or, nor, for, and yet) were rare or completely absent. Certain subordinating clauses covering a variety of relations (logical, temporal, locational) such as so that and where never showed up. Correlative conjunctions (neither/nor, both/and, whether/or, not only/but also, either/or) were missing.

Practice and reinforcement seemed to have an apparent effect on conjunction use. Conjunctions such as because and but disappeared in the entries after graduation.

| Most common subordinating conjunctions | Frequency |

| that | 53 |

| then | 19 |

| because | 16 |

| after | 13 |

| until | 6 |

| while | 5 |

| before | 4 |

| if | 3 |

| when | 2 |

| during | 2 |

| as soon as | 1 |

| since | 1 |

| although | 1 |

| even though | 1 |

| once | 0 |

| though | 0 |

| whether | 0 |

| so that | 0 |

| unless | 0 |

Table 2 | Use of subordinating conjunctions in corpus

Narrative structure

Narrative structure reveals much about the writer's ability to weave micro features of language into coherent units. Rose frequently used time indicators to organize her texts. She was very careful to identify how one occurrence related to another in time. The excerpt below, written when she was 19, shows why Rose used temporal indicators frequently. Her narratives did not simply proceed in a linear fashion but contained many temporal switches. Time markers are underlined and reported events numbered for discussion below:

Dear Journal,

1/27/2000

(1) I just received the card back from Mrs. Ryan and (2) everyone signed it. (3) Can you believe that (4) I have an FBLA meeting tomorrow morning? (5) It's already Thursday and (6) they just said (7) there is a meeting. (8) Why didn't they tell us members yesterday ?

(9) I have bowling today. (10) I can't wait because (11) on Sunday we have another bowling party. (12) I can't wait (13) until my father watches me bowl. (14) He'll be surprised *of me of how well I bowl. So good. Oh yeah!!

Love, Rose

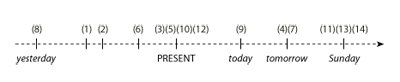

If we juxtapose the chronology of events against the order of presentation (numbered 1 to 14) in the journal entry, we can see why temporal indicators were necessary (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 | Chronology of events for the journal entry of 1/27/2000

As we can see in Figure 1, the time markers help the reader - and Rose - keep track of the events in relation to the present moment in this lively entry. The first proposition (I just received the card back...) is set just before the moment of speaking/writing. Nevertheless, Rose was still able to squeeze in two other events temporally (everyone signed it and they just said) before the present moment. In this particular excerpt, Rose was actually complaining of other people's scheduling of time, and her complaint in terms of clarity and rhetorical skill was handled competently.

In seven entries, slight omissions created a small degree of confusion in the chronology of events, as in the following excerpt written at age 21:

7/23/2002

We're going to Thomas Point today by boat. Mom and I sat on the beach and killed green heads. It was very humid and uncomfortable. It was really hot and we had quite a storm. It just stopped raining and the weather cooled off.

* Meanwhile, we went to the Laundromat and did some laundry. After that was done *We went shopping during the time that it rained. Now we're getting ready to eat dinner.

Meanwhile is insufficient here to indicate that the family went to the laundromat while it was raining. Only in the following sentence was it made clear. In fact, at this point, Rose felt the need to spell out explicitly during the time that it rained. Apart from this problem, there was still the conscientious effort to mark every sentence temporally. Even entries containing personal hopes, feelings and dreams contained temporal markers.

Rose's handling of time in her narratives matured when she began to work. In the following excerpt written three years after graduation, we see new elements emerging:

8/9/2005

Dear Diary,

Here at the beach for the last time of this vacation. I said, "It's delightful." "Laying out in the sun getting a tan, is wonderful." I replied, "I love it here in Maine and so does my family." Maybe I'll practice docking the boat with dad later. I would say, "If not, there's always tomorrow." Later, I'm going out for dinner to Kennebec Tavern. Mom and I said, "It's a lovely day and gorgeous."

Here Rose started off by framing the discussion, giving the place (at the beach) and time (last time of this vacation). What follows is less temporally constrained, unlike the entries written when she was younger. This is shown in the use of the gerunds (laying, getting), which carry no tense, and the declarative love. Rose then explicitly marked an activity taking place in the future (I'll practice later). Rose even dwelled on the hypothetical (I would say) if circumstances were to prevent her from practicing docking. She then returned to the timeless There's always tomorrow. To introduce a temporally bounded event (going out for dinner), she began the sentence with later. Immediately after, she switched back to her newfound less rigid style (It's a lovely day).

Rose showed no difficulty keeping track of the actors in her narratives. The corpus contained correct and consistent pronoun usage. Rhetorical features were also present, for example as manifested in the use of the second person:

As you can see I had my bowling pizza party. (5/30/2002)

Her writer's persona came across in her writing, especially after graduating from high school. Through her quotes, Rose wrote herself into the text:

Everybody said, "It's been three years since he caught a fish!" I said, "Hooray!" "Congratulations!" "Way to go Dad!" That's what I said to Dad…(8/6/2005)

Modality

Modality involves ways of marking the whole spectrum of truthfulness from straightforward factual statements to hedges, from hypothetical conditions to denials of truth. Modality is important to investigate here because it reveals the level of cognitive ability.

As can be discerned from the excerpts presented thus far, Rose's written language displayed a wide variety of devices to convey her thoughts. Her sentences were not merely simple statements of fact but represented a broad variety of forms, including probability and possibility:

It's supposed to snow on Wednesday, the 26 and Thursday, the 27…I'm hoping for a delayed opening. (1/24/2000)

I could probably look for a job just playing the piano. It's going to be very hard to find a job just playing the piano. (4/13/2000)

Rose also capably navigated through the varying degrees of certainty as carried by modal verbs. In the excerpt below, Rose used could when she was less sure of her abilities, can when she thought she was capable of doing something, and am when she was confident in her abilities:

I could stock or work as a cashier. I can help the customers to wrap presents.

I am very good when it comes to wrapping for birthdays and also for the holidays. I could work in an office, and I can file folders. I am a typist on the computer. (4/13/00)

On the other hand, Rose's use of negation was relatively simple. Rose utilized only real negatives: not (7/_/1998), couldn't (_/6/1998), and isn't (2/23/2004). Her writing completely lacked implicit negatives, such as rare or false, as well as partial negatives such as infrequent. Even for the sole negative form present in the corpus, i.e., not and its contracted variants, there were only eight occurrences. The majority were written while she was still in school.

Discussion

Owing to difficulties in speech production for persons with Down syndrome, their oral performance may not accurately reflect their actual competence [2] . Writing frees the writer from the constraints of real-time production and hence allows high-functioning persons with Down syndrome to display their linguistic abilities more fully. Through visual presentation, writing in addition helps compensate for their auditory and memory deficits.

Like many people with Down syndrome, Rose has a hearing impairment, which limits her ability to identify the exact words used in certain contexts. Function words are particularly affected because they are unstressed in natural speech and hence hard to pick out. Mishearing of full lexical words, as expected, involved confusion over phonetically related sounds, e.g., [b] for [v] in valance and [k] for [g] in gasket.

The present writing corpus did not contain the errors reported in Rondal's research [8] . Rondal noted problems with mechanics (punctuation and capitalisation), grammar, and spelling in Françoise's written text. There were relatively few such errors in Rose's writing, when accidental mistakes due to hasty writing were excluded. Rose's lexicon was varied, indicating a capacity to acquire and apply new words. Her sentence types also adequately fulfilled intended communicative functions. Nevertheless, the absence of certain forms point to certain processing or cognitive limitations. For example, the gaps in subordinate structure suggest difficulty with certain logical relationships and with linking two or more propositions together. The complete absence of correlative conjunctions is also understandable, since the writer would have to hold the first part (either/neither) while composing the second (or/nor) and vice versa. For the same reason, discontinuous constituents (e.g., so…that, not only…but also…) were also rare, being limited to the form if…then.

In their study of adolescents and adults with Down syndrome, Rondal and Comblain report that their subjects used negative sentences correctly only 36-57% of the time [14] . Rose was able to use negation correctly all of the time but the type of negation present in her writing was very limited. Language acquisition studies of typically developing children find that their negative sentences are significantly shorter than affirmative statements, indicating that negation increases structural complexity and hence cognitive effort [15 ].

In spite of these deficiencies, however, Rose's writing showed competent acquisition, control over sentence and text structures, and metalinguistic awareness. This is demonstrated in the variety of sentence types and their corresponding communicative functions. Rose's metalinguistic awareness is manifested in many ways: avoidance of forms that were likely to be produced incorrectly, control and organization of sentence and text structures, conscious monitoring of punctuation, and manipulation of modality. Contrary to Rondal and Comblain's conclusion that "the usual sequential narrative structure is not regularly used" in Down syndrome discourse, Rose used chronology as an effective strategy to produce and control text structure [14:p.6] .

Rose's avoidance strategy, complemented with the lack of exposure to certain linguistic forms in the special education classroom, resulted in the noticeable absence of certain phrases and structures. Nevertheless, given the level of proficiency Rose was able to achieve in spite of these limitations, it is likely that her true linguistic potential has yet to be realised.

In many respects, Rose's writing ability is comparable to that of typically developing children. One of the most comprehensive analyzes of the language of school children to date is Loban's seven-year study of 338 subjects and his 13-year study of some of his subjects' writing [11,12 ]. Rose, with an IQ score of 72, is within the range of that of Loban's Low Group (IQ range: 68-107). Rose actually exceeds this group's performance in terms of word density per sentence and absence of language mazes.

Early intervention programs are crucial for providing tools needed to learn, grow, and overcome any natural disadvantage. However, early intervention by itself is not going to make the difference that needs to be made. Rose's family provided for her the "natural settings for normally developing children" [16:p.164] , which instilled in Rose the idea that she was capable of any achievement when given the opportunity. Yet, we should also note the subtle gaps in her writing, possibly owing to the lack of exposure to adult communication in all its forms.

Concurrent with some detrimental effects from the lack of reinforcement after graduation, Rose's later writing showed, on the other hand, growing maturity such as a more fluid style and use of rhetorical devices. There are at present few higher education opportunities for people with Down syndrome. We can therefore only speculate on how the language of high-functioning persons might continue to mature if they are given the opportunity to continue with their education.

Conclusion

How much language deficits in persons with Down syndrome are attributable to biology and how much to the environment is still unclear, especially given the adverse effects of the compensatory strategies used by mothers of infants with Down syndrome [17] . Cerebral organization and physical impediments also hinder speech production and reception, in turn affecting caretakers' response as well as decreasing the expectations the community has for children with Down syndrome.

Based on the writing achievements reported here, it is apparent that the ceiling on linguistic development for some individuals with Down syndrome is higher than previously thought. By documenting in detail the writing of a high-functioning adult with Down syndrome, the present researchers aim to emphasize that learning is a lifelong endeavour. By illustrating how cognitive ability can be discerned from particular linguistic features and why larger, macro-structures of language production should be considered, we hope that this study would encourage similar investigations of other cases. We undertake this exploration because we genuinely believe that, if they are given the tools needed to develop fully, persons with Down syndrome are capable of exceeding our expectations.

References

- Farrell M, Elkins J. Literacy and the adolescent with Down syndrome. In: Denholm CJ, editor. Adolescents with Down syndrome: International Perspectives on Research and Programme Development. Victoria, BC: University of Victoria; 1991. p.15-26.

- Chapman RS, Hesketh LJ. Language, cognition, and short-term memory in individuals with Down syndrome. Down Syndrome Research and Practice. 2001;7(1):1-7. [Read Online ]

- Chapman RS. Language and cognitive development in children and adolescents with Down syndrome. In: Miller JF, Leavitt LA and Leddy M, editors. Communication Development in Children with Down Syndrome. Baltimore, Maryland: Brookes Publishing Company; 1999. p.41-60.

- Chapman RS, Sueng HK, Schwartz SE, Kay-Raining Bird E. Language skills of children and adolescents with Down syndrome: production deficits. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 1998;41:861-873.

- Gallaher KM, van Kraayenoord CE, Jobling A, Moni KB. Reading with Abby: a case study of individual tutoring with a young adult with Down syndrome. Down Syndrome Research and Practice. 2002:8(2);59-66. [Open Access Full Text]

- Fletcher H, Buckley S. Phonological awareness in children with Down syndrome. Down Syndrome Research and Practice. 2003:8(1);11-18. [Read Online]

- Clibbens J. Signing and lexical development in children with Down syndrome. Down Syndrome Research and Practice. 2001:7(3);101-105. [Read Online]

- Rondal JA. Exceptional language development in Down syndrome: Implications for the cognition language relationship. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1995.

- Rondal JA, Edwards S. Language in mental retardation. London: Whurr; 1997.

- Rondal JA, Comblain A. Language in aging persons with Down syndrome. Down Syndrome Research and Practice. 2002:8(1);1-9. [Read Online]

- Loban W. The language of elementary school children. Urbana, Illinois: National Council of Teachers of English; 1963.

- Loban W. Language development: kindergarten through grade twelve. Urbana, Illinois: National Council of Teachers of English; 1976.

- Shaughnessy M. Errors and expectations. New York: Oxford University Press; 1997.

- Rondal JA, Comblain A. Language in adults with Down syndrome. Down Syndrome Research and Practice. 1996:4(1);3-14. [Read Online]

- Bloom L. Language development from two to three. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1991.

- Vilaseca RM, Del Rio MJ. Language acquisition by children with Down syndrome: a naturalistic approach to assisting language acquisition. Children Teaching and Therapy. 2004;20(2):163-180.

- Moore DJ, Oates JM, Hobson RP, Goodwin J. Cognitive and social factors in the development of infants with Down syndrome. Down Syndrome Research and Practice. 2002;8(2):43-52. [Read Online]

Received: 8 March 2008; Revised version received 22 August 2008; Accepted: 29 August 2008; Published online: 17 December 2009

APPENDIX A | Journal entry with only a minor mechanical error:

APPENDIX B | Crossed-out journal entry: