Work stress and people with Down syndrome and dementia

This study aimed to assess how staff ratings of challenging behaviour for people with Down syndrome and dementia affected the self-reported well-being of care staff. Data were collected from 60 care staff in 5 day centres in a large city in England. The data were collected by use of a questionnaire. There was no significant difference between those who cared for individuals with Down syndrome and dementia and those caring for service users with other non-specified learning disabilities without dementia, regarding their self-reported well-being. Self-reported well-being did correlate with staff rating of challenging behaviour in both those who cared for people with Down syndrome and dementia and those who did not care for such service users, with well-being declining as perceived challenging behaviour increased. The findings indicate that challenging behaviour prevention and reduction may be of benefit to both service users and care staff well-being.

Donaldson, S. (2002) Work stress and people with Down syndrome and dementia. Down Syndrome Research and Practice, 8(2), 74-78. doi:10.3104/reports.133

Introduction

In the learning disabilities services staff are the most expensive resource. Emerson et al. (1999) suggested that in dispersed housing schemes staff account for 72% of expenditure. A number of factors have been shown to influence staff well-being including support (Rose, 1999), confidence (Sistler & Washington, 1999), gender of caregivers (Sharpley, Bitsika & Efremidis, 1997) and coping strategies (Wright, Lund, Caserta & Pratt, 1991). There are clearly many other factors (for a review see Rose, 1997). Although all of these factors have been investigated in the literature with regard to general stress experienced by those caring for people with learning disabilities, there is a dearth of literature concerning the well-being of caregivers specifically caring for people with Down syndrome and dementia.

Down syndrome and dementia

"There is considerable evidence that adults with Down syndrome are at increased risk of developing acquired cognitive impairments consistent with dementia as they age" (Oliver, 1998). Oliver found that during the four-year study period 70% of those over the age of 50 acquired cognitive impairments. Thase, Smeltzer and Maloon (1982) suggested that there is a clear deterioration in neuro-psychiatric status with advancing age in people with Down syndrome when compared to control participants. They concluded that overall individuals with Down syndrome were twice as likely to have at least one sign or symptom of dementia and twelve times more likely to have a full syndrome of dementia.

Client characteristics and staff well-being

Clients possess a number of attributes, which may impact on the well-being care staff experience. The problems highlighted by caregivers and service users clearly indicates that it is the area of mental health, behavioural problems and basic daily living skills that challenge carers (Oliver, 1998). Oliver stated that of the carers that were experiencing problems and needed help, 80% indicated that help was needed in the area of difficult behaviour and mental health. Oliver, Crayton, Holland and Hall (2000) reported that difficulty for caregivers was associated with cognitive and behavioural problems in service users. One of the many characteristics facing care staff within learning disabilities services is that of challenging behaviour.

An extensive amount of research has looked at the effects of challenging behaviour on caregiver well-being, (Jenkins, Rose & Lovell, 1997). This research is not restricted to learning disabilities but encompasses most services where caregivers are involved (Hinchliffe, Hyman, Blizard & Livingston, 1992). Research with direct-care staff working with people who had learning disabilities and challenging behaviour, indicated that those staff working in houses where there was a known history of challenging behaviour reported more anxiety than staff in non-challenging behaviour houses (Jenkins et al., 1997). These findings suggest that the presence of challenging behaviour may have an effect on care staff.

It has been argued that the most common source of stress for those caring for individuals with challenging behaviour was the absence of an effective way to deal with challenging behaviour and the unpredictability of such behaviour (Bromly & Emerson, 1995). Hinchliffe et al. (1992) investigated the use of psychological and pharmacological methods of managing behaviour reported that there was an association between clinically significant changes in service users' behaviour and a fall in caregiver General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) score. This suggested that a reduction in challenging behaviour exhibited by the client may reduce the burden experienced by staff. Closer investigation of this study reveals a clinically significant change in client's behaviour and a reduction in caregiver's GHQ score was only seen in three cases (out of sixteen). The finding therefore could have been the result of characteristics possessed by the caregivers rather than attributable to the intervention used. It would therefore be unwise to generalise from these observations to those people with behavioural difficulties as a whole without testing a larger population first. Although some support for the findings is provided by Jenkins et al. (1997), the use of different measurements for both resident characteristics and staff well-being may lessen the comparability of the results. In contrast Chung, Corbett and Cumella (1996) found that although burnout was high, staff had a positive outlook towards working with clients, with burnout being correlated with management issues (e.g. hours worked, training received) rather than clients' behaviour. This finding was duplicated by Chung and Corbett (1998) in a later study, and supported by Rose (1997) in a review of the literature.

The present study

In light of increasing concerns over the well-being of caregivers, and the observation that care staff who work with people with Down syndrome and dementia can appear to be more stressed than those who do not (Oliver, 1998), it has been proposed that staff perceptions of challenging behaviour, as exhibited by people with Down syndrome and dementia will be examined in relation to the impact such perceptions may have on psychological well-being of the caregiver.

Method

Design

A survey design was adopted comparing two groups of staff working with people with learning disabilities in day centres. One group included staff working with service users with Down syndrome and dementia (Down syndrome and dementia group), and the second group included staff working with service users with other non- specified learning disabilities, but not Down syndrome, and without dementia (learning disabilities group).

Selection and description of day centres

Day centres were selected on the criteria that they contained service users with Down syndrome and dementia. All of the day centres selected were in a large city in England. A total of five social services run day centres were approached, and the agreement of both social services and each of the centres was sought. Of the 113 care staff approached 60 questionnaires were completed (53% return rate).

Procedure

Questionnaires were distributed to staff on an individual basis. A small number of questionnaires were left with managers for distribution to those staff that wished to participate in the study but were not present on the day of distribution. It was explained to those members of staff present that the questionnaire was anonymous and that no names needed to be supplied. An explanatory letter for the benefit of those members of staff not present on the day of distribution and an envelope were attached to the questionnaire. The author was present to assist distribution and to answer any queries. On completion of the questionnaires participants were asked to seal the questionnaires in the envelopes provided and return them to managers for collection by the author.

Research measures

Staff perception of challenging behaviour in people with and without Down syndrome and dementia

The first question established whether staff worked with service users with Down syndrome and dementia. If they did, did they deem the service user they had most contact with exhibited challenging behaviour. This was a simple yes/no distinction. The decision of what constituted challenging behaviour was left to the professional judgement of the individual respondent. Those members of staff who answered yes were asked to continue to the next question, which asked staff to rate how challenging they perceived the service user to be. Staff perception of challenging behaviour was assessed using a six point likert scale. The scale ranged from not challenging to extremely challenging. Perceived challenging behaviour of service users with other non-specified learning disabilities was also assessed by the same procedure and likert scale as described above.

The Thoughts and Feelings Index

The Thoughts and Feelings Index (Fletcher, 1989) was used to assess psychological well-being. This is a short questionnaire, measuring anxiety and depression levels. The questionnaire consists of eight statements: four comprise the depression subscale, and four comprise the general anxiety subscale. Caregivers were asked to indicate how often each of the eight statements applied to them by use of a four-point scale, ranging from never to very frequently/often. The maximum score on each of the two scales is sixteen. A score of above 12 is of clinical significance.

The General Health Questionnaire

The General Health Questionnaire 12 (Goldberg, 1978), concentrates on broader components of psychiatric morbidity, including particularly anxiety and depression. The questionnaire is made up of 12 statements asking participants to compare their recent medical complaints to their usual state on a 4-point scale of severity. Some of these items are positive and some negative. Scores of four and above (when using the GHO-12 scoring system) are of clinical significance, with higher scores indicating decreased well-being.

Results

The general characteristics of the sample

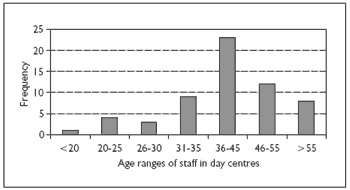

Completed questionnaires were returned by 60 caregivers. In this sample 35 members of staff were female (58%) and 25 were male (42%), 51 members of staff were full time (85%) and 9 were part time (15%). There was a broad distribution of age in the sample (Figure 1), with 36-45 years being the modal category. Of the staff 35% (n=21) had been working at their current place of occupation for less than two years, 17% (n=10) for two to five years and 48% (n=29) for more than five years.

Figure 1. Age distribution of care staff in day centres

Those specifically working with Down syndrome and Dementia service users

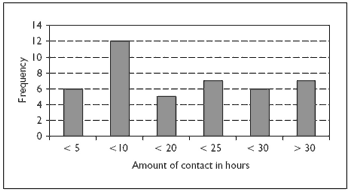

Of the 60 staff in the survey, 43 members of staff worked with service users who had Down syndrome and dementia. Of these individuals, 21 (48%) were key workers and 22 (52%) were non-key workers. Three of these individuals (7%) had worked with people with Down syndrome and dementia for less that 3 months, 5 (12%) had worked with service users for less that 6 months, 7 (16%) for less than a year, 4 (9%) for less that two years, 5 (12%) for less than three years and 19 (44%) members of staff had worked with Down syndrome and dementia service users for three years or more. The amount of contact staff had with service users varied (Figure 2), with the mode amount of contact being less than 20 hours. Of the 43 members of staff who worked with service users with Down syndrome and dementia 31 (52%) of them worked with a service user who they felt also exhibited challenging behaviour.

Figure 2. Amount of contact care staff had with service users with Down syndrome and dementia

Descriptions of psychological well-being

The mean Anxiety score for all staff in the study was 9.18, and 13% (n = 8) had a score that was clinically significant (i.e. above 12). The mean Depression score for all staff was 7.56 and 3% (n = 2) had a score that was clinically significant (above 12). The average GHQ score for the 60 staff members was 0.93 (using the likert scoring method), and 25% (n= 15) had scores that were clinically significant (i.e. 4 and above using the GHQ-12 scoring method).

Comparison of Down syndrome and dementia group with the learning disabilities group

The first analyses compared the Down syndrome and dementia group (n = 43) with the learning disabilities group (n = 17). There was no significant difference between them when compared on the psychological well-being scales of Anxiety (t(58)=0.19 n.s.), Depression (t(58)=0.41 n.s.) or GHQ-12, (t (58)=0.378 n.s.).

Comparison using self-reported presence of challenging behaviour

The Down syndrome and dementia group was split further into two groups for analysis. Those staff who responded 'yes' to the question "has the service user with Down syndrome and dementia ever exhibited challenging behaviour" were placed in the Down syndrome, dementia and challenging behaviour group (72% n = 31). Those who answered 'no' to the question were placed in the non-challenging behaviour group (28% n = 12). There was no significant difference between the groups when compared on the psychological well-being scales of Anxiety (t(41)= -0.039, n.s.), Depression (t(41)=0.184, n.s.) or GHQ-12 (t(41)=0.149, n.s.).

The challenging behaviour group (n = 31) was further examined. A Pearsons correlation was performed between the psychological well-being scales and staff perception of challenging behaviour exhibited by service users with Down syndrome and dementia. The reported level of challenging behaviour was significantly correlated with the GHQ-12 (r = .36, p < .05). That is, as perceived challenging behaviour increases self-reported well-being decreases. There was no significant correlation between perceived level of challenging behaviour and Anxiety (r=0.25, n.s.) or Depression (r=0.29, n.s.).

Impact of service users with learning disabilities on care staff well-being

All care staff were asked if they worked with another client with learning disabilities that exhibited challenging behaviour but who did not have Down syndrome and dementia, and 54 of the 60 (90%) staff who filled in the questionnaire did. As with the previous section, a Pearsons correlation was conducted between, how challenging staff perceived the service user to be and the psychological well-being measures of Anxiety, Depression, and the GHQ-12. Perceived level of challenging behaviour in service users with learning disabilities was significantly correlated with Depression (r = .30; p<.05), and the GHQ-12 (r = .35; p < .01), but not with Anxiety (r = .10. n.s).

Discussion

The analysis of the difference between those caring for people with Down syndrome and dementia and those caring for people with non-specified learning disabilities suggests that the well-being experienced by both these groups is similar irrespective of the client group they are caring for. When looking at the Down syndrome group specifically in relation to the presence or absence of challenging behaviour, no significant difference was observed in carers' well-being. This suggests that the mere presence of challenging behaviour is not mediating the well-being of care staff.

The findings of the correlation analysis suggest that as perceived level of challenge for service users with Down syndrome and dementia increases, care staff well-being tends to worsen. The results for those staff caring for service users with learning disabilities with challenging behaviour, but who do not have Down syndrome and dementia, also follow this pattern, in that, when challenging behaviour is present, as the perceived level of challenge increases the well-being of care staff worsens. This is not an unexpected finding as one might speculate that as the level of challenging behaviour, whether this be perceived or actual, increases from not challenging to extremely challenging the well-being of care staff will diminish. This finding is similar to others in the literature, with authors such as Oliver et al. (2000) suggesting that the difficulties experienced by caregivers may be associated with cognitive and behavioural problems experienced by the service users. However, it may alternatively be argued that it is the well-being of caregivers which is affecting how challenging service users are perceived.

The aim of the present study was to try to explore whether perceived challenge presented by service users with Down syndrome and dementia had an impact on the psychological well-being of care staff. The above findings suggest however that when behavioural difficulties are present, it is the perceived degree of these behavioural difficulties that is important in mediating the psychological well-being of care staff in this cohort, whether service users have Down syndrome and dementia or not. The findings would imply that challenging behaviour prevention and reduction might not only be useful for service users, but also for staff well-being. This finding is supported by the literature, in that the degree of challenging behaviour is a predictor of psychological well-being in staff (e.g. Jenkins et al., 1997, Hinchliffe et al., 1992).

There are a number of reasons why when specifically looking at caregivers of people with Down syndrome and dementia compared to other service users with learning disabilities no significant results were observed. The first is that as service users cognitive abilities decline and behavioural problems increase, they are less likely to attend day centres. Oliver et al. (2000) reported that individuals experiencing cognitive decline were less likely to receive day services. This suggests that although service users with Down syndrome and dementia will be present in this sample, they may be less distressed, and may show less complex problems than those in residential or nursing care. Secondly the organisation of day centres is such that there is often considerable mobility between groups. Care staff are often involved with different groups and activities on a daily basis, and the service users themselves may only be present for a set number of days a week, or involved in activities which removes them from the centre, or the care of the staff member. Finally, researchers have argued (e.g. Chung et al., 1996) that a positive attitude to working with such service users reduces the impact of challenging behaviour on psychological well-being and that psychological well-being is more associated with management issues (a factor not assessed in this study) than clients' behaviour.

There are some limitations of this study, during the data collection period day centres in the sample area were under considerable organisational uncertainty, the nature of these changes were undisclosed, but likely to have had an effect on the stress scores of many participants. It should also be acknowledged that the focus of the study was on the effects of a specific factor, namely perceived challenging behaviour, on the well-being of care staff working in day centres, the problem however is that well-being is complex. There was no investigation of other factors either internal or external to the day centres that could have had an impact on care staff well-being. This is an important consideration, as outside influences (such as home environment) will undoubtedly have an impact on individual well-being.

There are a number of areas that require future research and day care for service users with Down syndrome and dementia is a neglected area of investigation. The present study has focused on but one of the many factors associated with well-being. Further research in this area should therefore look at other factors which mediate the service user-caregiver interaction, for example how supported staff feel they are by managers, or the conflicting demands of work and home, with an aim to identify which are important in mediating staff well-being. Identification of these factors will enable interventions within day centres to have enhanced effectiveness. There is also a need to assess well-being longitudinally, as service users with Down syndrome and dementia experience greater cognitive deterioration and increased behavioural problems, how will caregiver well-being be effected? Such research will clarify the stages at which intervention programmes are most needed, as service users with Down syndrome and dementia pass through different levels of care.

Acknowledgements

The present study was conducted as part of a BSc (Hons) Psychology degree conducted at the University of Birmingham. I would like to thank all caregivers that took part in the study, Dr John Rose for his supervision, as well as Professor Chris Oliver, Dr Sunny Kalsy, and Paul Dolan for their help on the project.

Correspondence

Stephen Donaldson • 67 Sparrey Drive, Bournville, Birmingham B30 2LX

References

- Bromly, J., & Emerson, E. (1997). Beliefs and emotional reactions of care staff working with people with challenging behaviour. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 39, 341-352.

- Chung, M.C., & Corbett, J. (1998). The burnout of nursing staff working with challenging behaviour in hospital based bungalows and a community unit. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 35, 56-64.

- Chung, M.C., Corbett, J., & Cumella, S. (1996). Relating staff burnout to clients with challenging behaviour in people with a learning disability: Pilot study. European Journal of Psychiatry, 10, 155-165.

- Emerson, E. (1995). Challenging Behaviour: Analysis and Intervention in People with Learning Disabilities. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Emerson, E., Robertson, J., Gregory, N., Hatton, C., Kessissoglon, S., Hallen, A., Knapp, M., Jarbrink, K., Netten, A., & Noanan Walsh, P. (1999). Quality and Costs of Residential Supports for People with Learning Disability. Manchester, UK: Hester Adrian Research Centre, University of Manchester.

- Fletcher, B.C. (1989). The Cultural Audit: An Individual and Organisational Investigation. Cambridge, UK: PSI.

- Goldberg, D. (1978). General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12). Oxford, UK: NFER-Nelson.

- Hinchliffe, A.C., Hyman, I., Blizard, B., & Livingston, G. (1992). Impact on carers of behavioural difficulties in dementia: A pilot study on management. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 7, 579-583.

- Jenkins, R., J, Rose., & Lovell, C. (1997). Psychological well-being of staff working with people who have challenging behaviour. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 41, 502-511.

- Oliver, C. (1998). Ageing in adults with Down syndrome. [Online]. Available: The Mental Health Foundation. https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/brief017.htm [Accessed: 2000, November 7. Please note: this link is not longer active - to view this article visit https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/ then conduct a search for 'ageing'].

- Oliver, C., Crayton, L., Holland, A., & Hall, S. (2000). Cognitive deterioration in adults with Down syndrome: Effects on the individual, caregivers, and service use. American Journal on Mental Retardation, 105 (6), 455-465.

- Rose, J. (1997). Stress and stress management among residential care staff. Tizard Learning Disability Review, 2 (1), 8-15.

- Rose, J. (1999). Stress and residential staff who work with people who have an intellectual disability: A factor analytic study. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 43, 268-278.

- Sharpley, C.F., Bitsika, V., & Efremidis, B. (1997). Influence of gender, parental health and perceived expertise of assistance upon stress, anxiety and depression among parents of children with autism. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 22, 19-28.

- Sistler, A., & Washington, K.S. (1999). Serenity for African American caregivers. Social Work with Groups, 22, 49-62.

- Thase, M.E., Smeltzer, L.L.D., & Maloon, J. (1982). Clinical evaluation of dementia in Down syndrome: A preliminary report. Journal of Mental Deficiency Research, 26, 239-244.

- Wright, S.D., Lund, D.A., Caserta, M.S. & Pratt, C. (1991). Coping and caregiver well-being: Impact of maladaptive strategies. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 17, 75-91.