The early reading skills of preschoolers with Down syndrome and their typically developing peers - findings from recent research

Some early readers with Down syndrome find 'sight word' learning very easy and it appears to have very positive effects on the development of their spoken language skills and general cognitive development. This research study shows that preschool children with Down syndrome are able to learn sight words just as fast as age matched typical preschoolers.

Appleton, M, Buckley, S, and MacDonald, J. (2002) The early reading skills of preschoolers with Down syndrome and their typically developing peers - findings from recent research. Down Syndrome News and Update, 2(1), 9-10. doi:10.3104/updates.157

The issue of early 'sight word' reading, beginning in the preschool years, discussed in the individual case studies, needs further consideration. Some early readers with Down syndrome find 'sight word' learning very easy and it appears to have very positive effects on the development of their spoken language skills and general cognitive development. A recent research study [1, 2] shows that preschool children with Down syndrome are able to learn sight words just as fast as age matched typical preschoolers.

Reading progress

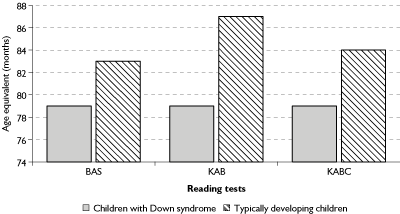

The progress of 18 children with Down syndrome was compared with the progress of 18 typically developing children of the same age (2 to 4 years, mean age 4 years 1 month), when their parents taught them to read a 'sight vocabulary' with the researcher's support. In the first year of the study, both groups progressed at the same rate. After six months the average 'sight vocabulary' learned was 15 words for the typically developing group and 17 words for the children with Down syndrome. There were large individual differences in the number of words learned in both groups. Some children learned no words and some learned 66 or 67 words, in both the typically developing group of children and those with Down syndrome. By the third year of the study, when the average age of the children was 6 years 7 months and they were in school, the progress of the readers in the two groups (defined as those who can score on reading tests) was compared. These readers (16 of 17 typically developing children and 11 of 18 children with Down syndrome) are at a similar level for reading and for reading comprehension on standardized tests (see Figure 1). Their test scores are not statistically significantly different from one another and the children with Down syndrome are reading at their age level.

Figure 1. Preschool readers - progress at 6 years. The group differences are not significantly different - the readers with Down syndrome are in the same range as the typically developing children and reading at their age level

Key: BAS: British Ability Scales Reading; KAB: Kaufman Assessment Battery Reading; KABC: Kaufman Assessment Battery Comprehension

This data supports the view that reading ability is a significant strength for children with Down syndrome and that, for many, the visual discrimination and visual memory skills needed to learn sight words are not delayed for their age. At the stage when all children's reading progress is largely supported by logographic skills (sight word reading), the readers with Down syndrome (61% of the group) are keeping up with their peers on reading and on reading comprehension. Their progress supports the evidence that visual processing and visual memory skills are less impaired than other areas of their cognitive skills and should definitely be used to support all learning.

Do we have evidence of benefits for spoken language?

There is some evidence that reading progress is having an influence on spoken language development from the data collected during this study. The children with Down syndrome who go on to become readers are not significantly different (in statistical terms) on the language measures at the start of the study as there is wide variation in the abilities of both groups of children. However, on average, the readers are ahead by 2 months on the Reynell Expressive Language measure and by 6 months on the Reynell Comprehension measure at the start of the study. After 3 years, the readers are now 8 months ahead of the non-readers on Expressive Language and 11 months ahead on Comprehension.

Can we predict reading success?

We do not know why some children with Down syndrome remained non-readers. The non-readers as a group scored significantly lower on a general mental ability test at the start of the study but not at the end, though their mean scores were still lower than the readers. However, if we looked at the lowest scorers on the mental ability tests, 2 became readers while 4 did not. Our findings do not allow us to predict who will become readers and who will not from their scores on language or mental ability tests at the start of the study. We do not have any firm data on how often parents of any of the children actually found time to teach their children, though we encouraged a minimum of 5 to 10 minute sessions, 3 times a week. Daily practice is the ideal, just for short periods of time.

In summary

The findings from this study suggest that the visual discrimination and visual memory skills which support early sight word reading are a strength for children with Down syndrome and they are as good at learning printed words as their age matched typically developing peers. There is also evidence that reading progress had a positive influence on the rate of spoken language development, including expressive language. It was not clear why some children became readers and others did not - a more detailed study, recording the time spent in reading activities and documenting progress more frequently might shed some light on this issue.

Early start

It may be particularly important to begin to use reading activities by the age of 3 years in order to have the maximum effect on the children's speech and language development, as the years between 2 and 7 are the time when researchers into child language development believe that the brain may be most ready to develop language, particularly grammar and phonology. This argument has been explained more fully by the second author in a review of the literature on speech and language development in children with Down syndrome. [3] In the authors' experience, the children with Down syndrome who are exposed to early language teaching through reading from this young age do make the greatest progress with reading, writing and speaking in their school years.

Benefits at any age

However, other research suggests that reading activities will still have a significant beneficial effect on spoken language development if started in the school years [4, 5] , therefore it is never too late to engage children and teenagers with Down syndrome in meaningful reading activities and practical guidance is available for, preschoolers, 5 to 11 year olds and teenagers in the new Down Syndrome Issues and Information series (see Reading Resources).

References

- Appleton, M. (2000) Reading and its relationship to language development: A comparison of pre-school children with Down syndrome, hearing impairment or typical development. Unpublished M.Phil. Thesis. University of Portsmouth, UK.

- Whitcombe, M., Buckley, S. J., & MacDonald, J. (1999). A three year longitudinal study of reading development among pre school children with Down syndrome and pre school typically developing children. Presented at the Fourth European Down Syndrome Conference, Malta.

- Buckley, S.J. (2001) Speech and language development for individuals with Down syndrome - An overview. The Down Syndrome Educational Trust, Portsmouth, UK.

- Laws, G., Buckley, S. J., Bird, G., MacDonald, J., & Broadley, I. (1995). The influence of reading instruction on language and memory development in children with Down syndrome. Down Syndrome Research and Practice, 3(2), 59-64. [Read Online]

- Buckley, S.J. (2002) An overview of the development of teenagers with Down syndrome (11-16 years). Down Syndrome Education International, Portsmouth, UK. ]