What's it all about? Investigating reading comprehension strategies in young adults with Down syndrome

The purpose of reading is for the reader to construct meaning from the text. For many young adults with Down syndrome, knowing what the text is all about is difficult, and so for them the activity of reading becomes simply the practice of word calling. It is suggested in the literature that for those individuals with Down syndrome, learning can continue into adolescence and that this may be the optimal time for learning to occur. However, a review of the literature revealed limited empirical research specifically relating to the reading comprehension of young adults with Down syndrome. Recent findings from Latch-OnTM(Literacy And Technology Hands On), a research-based literacy and technology programme for young adults with Down syndrome at the University of Queensland, revealed that comprehension remained the significant area of difficulty and showed least improvement (Moni & Jobling, 2001). It was suggested by Moni and Jobling (2001) that explicit instruction in comprehension using a variety of strategies and meaningful, relevant texts was required to improve the ability of young adults with Down syndrome to construct meaning from written texts. This paper is based on an action research project that was developed within the Latch-OnTM programme. The project utilised a modification of Elliot's (1991) action research model and was conducted to investigate specific teaching and learning strategies that would enhance the reading comprehension of young adults with Down syndrome. The participants were 6 young adults with Down syndrome ranging in age from 18 to 25 years. As the data from this project are still being analysed, preliminary findings of one participant are presented as a case study. The preliminary findings appear to indicate that the programme of specific teaching and learning reading comprehension strategies used in this project was beneficial in the participant's reading comprehension.

Morgan, M, Moni, K, and Jobling, A. (2004) What's it all about? Investigating reading comprehension strategies in young adults with Down syndrome. Down Syndrome Research and Practice, 9(2), 37-44. doi:10.3104/reports.290

Introduction

For individuals with intellectual disabilities such as Down syndrome the establishment of effective pedagogies and strategies for the teaching and learning of reading comprehension is vital due to various difficulties they encounter in learning. Over the past two decades, despite considerable research into reading comprehension, knowledge of the need for explicit instruction and the testing of comprehension in schools, there remains limited provision of explicit instruction in reading comprehension (Chard & Kame'enui, 2000; Pressley, Wharton-McDonald, Hampston & Echevarria, 1998; Vaughn, Moody & Schumm, 1998).

Although it is recognised that comprehension needs to be addressed and that for this population adolescence may be the optimal time for learning to occur, there has been limited specific research about effective pedagogies and strategies for teaching and learning with this group (Moni & Jobling, 2001; Fowler, Doherty & Boynton, 1995; Bochner, Outhred & Pieterse, 2001).

Others have suggested that even with proficient word recognition skills and high levels of reading accuracy, young adults with Down syndrome still find it difficult to recall details of text (Farrell & Elkins, 1994/1995; Farrell, 1996). This difficulty has been well documented by several authors who report that individuals with Down syndrome experience difficulties in tasks that require the use of working memory (Bird, Beadman & Buckley, 2001; Broadley & MacDonald, 1993; Tunmer & Hoover, 1992). Comprehension is one such task.

Thus, reading comprehension remains the significant area of difficulty for this population and there is a recognised need for specific reading interventions for students who are learning disabled (Farrell & Elkins, 1994/1995; Levy & Chard, 2001; Torgesen, Wagner, Rashotte, Alexander & Conway, 1997)

Predominantly, in studies that have focussed on the teaching of reading to students with learning disabilities, the findings have reported on whole language based approaches to reading where there is limited instruction in comprehension. The studies also found that between typically developing students and students with special needs there was minimal differentiation in the methods of instruction and in the selection and use of materials (Moody, Vaughn, Hughes & Fischer, 2000; Vaughn et al., 1998).

In an Australian study, van Kraayenoord, Elkins, Palmer and Rickards (2001) found that many students with learning disabilities were expected to achieve the same learning outcomes as typically developing students and that often the teaching strategies were the same for both groups of students. The findings of this study supported the need for teachers to adapt their teaching strategies to meet the individual needs of students with disabilities.

A socio-cultural approach for the development of literacy learning in students with intellectual disabilities was advocated by Moni and Jobling (2000) and van Kraayenoord, Moni, Jobling and Ziebarth (2001). The basis of a socio-cultural approach is the creation of an understanding that literacy activities must be meaningful to the participants and have purposeful outcomes. Through this approach students are able to make meaningful connections between their personal lives and the literacy activities with which they engage and as a result, motivation remains high because the texts are chosen or developed around the students' chosen interests with outcomes that are relevant to them (Moni & Jobling, 2000). The Latch-On TM programme is a practical and successful example of the benefits of a socio-cultural approach to the literacy learning of students with intellectual disabilities. This approach does much to address some of the requirements for the development of literacy in young adults, however based on the findings of Moni and Jobling (2001) it appears that additional teaching and learning strategies may be needed for the specific development of reading comprehension in young adults with Down syndrome.

In this regard, other authors have highlighted the need for the use of prior knowledge and past experiences, prediction and knowledge of story grammar components while reading to assist students in reading comprehension (Fournier & Graves, 2002; Gersten, 2001; Nguyen Bui, 2002; Polloway, Patton & Serna, 2001; Worthing & Laster, 2002). While positive effects on the comprehension of children and teenagers with learning disabilities have also been reported using story maps (Gardill & Jitendra, 1999), graphic organisers (Doyle, 1999), and pictures (Bird, Beadman & Buckley, 2001) the limited available research suggests that more could be done to improve the reading comprehension of individuals with Down syndrome.

This paper is based on an action research project that was developed within the Latch-On TM programme. The project utilised a modification of Elliot's (1991) action research model and was conducted to investigate specific teaching and learning strategies that would enhance the reading comprehension of young adults with Down syndrome.

Participants

The participants were 6 young adults with Down syndrome ranging in age from 18 to 25 years. There were 4 males and 2 females. They all attended Latch-On™ and were nearing completion of their first year of the programme at the commencement of the research project. The age equivalent for the receptive language of the participants, measured by the PPVT IIIA (Dunn & Dunn, 1997) as part of the Latch-On™ program, ranged from 4 years to 8 years 10 months. Their reading ages for accuracy, measured by the Neale Analysis of reading - 3rd edition (Neale, 1999), ranged from 6 years 9 months to 10 years 11 months. As the data from this project are still being analysed, preliminary findings of one participant, Lewis, 1 are highlighted as a case study. This participant was male and aged 19 years and 6 months at the start of the study. Lewis' age equivalent for receptive language, measured by the PPVT IIIA (Dunn & Dunn, 1997) was 8 years 0 months. His results from the Neale Analysis of Reading - 3rd edition (Neale, 1999) are discussed in detail in the following sections.

Data collection instruments

A participant reading interview, parent/guardian questionnaire and retelling assessment criteria were specifically designed for the current project, and further details of the design of these can be found in the following sections.

In addition, the participants were assessed using the following standardised measures of reading:

- The Neale Analysis of Reading, 3rd edition (Neale, 1999) which measures reading accuracy, comprehension and reading rate;

- The Burt Word Reading Test-1974 revision (Burt and the Scottish Council for Research in Education, 1976) which is a test of word recognition in which the words are presented singularly; and

- The Waddington Diagnostic Reading Test (Waddington, 1988) which tests reading comprehension and word recognition. It combines selecting and matching words to pictures, reading and completing nursery rhymes and selecting the correct missing word from up to ten choices in increasingly complex sentences and topics.

Method

The project was conducted within the socio-cultural teaching environment of the Latch-On TM programme. It utilised an ABA (pre-test, intervention, post-test) design within an action research methodology based on a modification of Elliot's (1991) model.

Phase A

A participant reading interview and a parent/guardian questionnaire were designed by the first author and conducted to determine the reading experiences, attitudes and behaviours of the participants. The LANDA project (1990) and van Kraayenoord (1992) were consulted as guides to the development and design of these measures.

Data pertaining to the reading skills of the participants were collected through a combination of standardised testing, the re-telling of a short written narrative text (Wilson, 1987 "My Dog's in Trouble") to which story categories were applied that were based upon simple story grammar components (Nguyen Bui, 2002) and participant observation (Elliot, 1991; Hopkins, 2002). The selection of the text was made following consideration of reading needs, interests and behaviours of the participants as determined from an analysis of the data collected from the participant interview, parent/guardian questionnaire and observation of the participants within the Latch-On TM programme.

All data with the exception of the parent/guardian questionnaire were collected in a one-on-one situation with the assistance of video recording throughout.

Phase B (Intervention phase)

As is the nature of action research, data were constantly gathered and analysed throughout each phase of the project (Elliot, 1991; Hopkins, 2002). The effectiveness of teaching strategies and the presentation of these together with learner activities and behaviour were a focus of the intervention. All sessions were video taped as an aid to participant observation, to capture the teaching changes, adaptations and responses made, how they were made, why they were made and the positive or negative effects they had on the participants. Written observations were made from the videos, analysed and reflected upon in the next "reconnaissance" phase of the action research model.

Phase C

Data collection pertaining to the reading skills of the participants were repeated using the same combination of measures taken at Phase A, with the exception of the participant interview and parent/guardian questionnaire.

The intervention

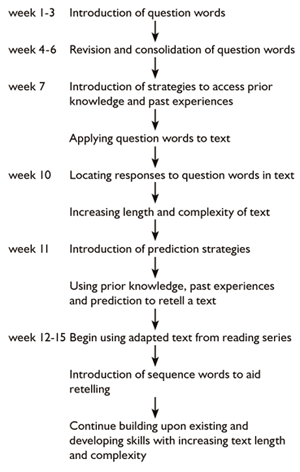

Figure 1 | Intervention overview flow chart

The intervention phase reported here was conducted over a 15 week period. Figure 1 provides an overview of the intervention phase. The participants attended one session per week. The duration of each session averaged 15 to 30 minutes and the participants attended in pairs until week 12. From week 12 the participants were extending their retelling to longer, adapted text from a reading series (Wilson, 1980-1997). The reading series was selected based upon knowledge of the participants' reading needs, interests and behaviours gathered from the data collected in Phase A. At this stage they attended sessions individually to further meet individual needs, promote confidence in their own abilities and avoid potential influence from each other.

Based on the available research, three key concepts were chosen and used to frame the intervention strategies used with the participants. These three key strategies were:

- The use of question words to access prior knowledge and past experiences. For example " Where do you go to get a hamburger?" "In the canteen shop at the Uni".

- The use of prediction to make links between prior knowledge and past experiences to assist in the construction of meaning from the text. For example, "This story is called 'The Lake'. What might you do at the lake?" "Catch a fish."

"We've written our guesses about what might be in the story on the board. Let's read the story and see if we guessed what it might be about." - The use of re-telling of a text to recall details of the text and assist in the construction of meaning from the text. For example, "Tell me about the story". " Well it's all about his father and his dog. The dog does stupid things on that day."

Results

Lewis: A case study

These preliminary findings will be reported in tabulated form, showing a comparison of standardised pre-testing and post-testing results, and participant observations as they relate to Lewis' performance. These observations were used as a qualitative tool and focused particularly on the effectiveness of the key strategies of accessing prior knowledge and past experiences, prediction and re-telling from the intervention phase.

| Pre-intervention | Post-intervention | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CA a | Accuracy | Comp b | Rate c | CA | Accuracy | Comp | Rate |

| 19:6 | 7:0 | 6:9 | 13+ | 20:9 | 7:10 | 7:9 | 13:1+ |

a Chronological Age b Comprehension c Rate refers to fluency or speed of reading

Table 1 | Chronological and reading ages (years: months) on the Neale Analysis of Reading Ability , 3rd edition (1999)

Standardised testing

Table 1 shows improvement in Lewis's performance in all aspects of the Neale Analysis of Reading, 3 rd edition (1999). Following the intervention Lewis showed gains in accuracy of 10 months and in comprehension of 12 months. His reading rate remained well above the ceiling level. While all results remain well below his chronological age the improvements in reading accuracy and comprehension are encouraging.

Table 2 shows the results from the 3 different reading tests. Only the accuracy element of the Neale Analysis of Reading Ability has been reported here.

Again, Lewis has made gains in all of the three tests. The gains made in the Neale Analysis of Reading Ability (accuracy element) and Burt Word Reading tests were similar with gains of 10 and 9 months respectively. Lewis also made a gain of 4 months in the Waddington Reading test, with a mean gain across the three tests of 8 months.

| CA | Neale | Burt | Wadd | Mean a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-intervention | 19:6 | 7:0 | 8:7 | 8:0 | 7:10 |

| Post intervention | 20:9 | 7:10 | 9:4 | 8:4 | 8:6 |

a the mean reading age across all three reading assessments for Lewis

Table 2 | A comparison of reading ages (years: months) across reading tests pre- and post-intervention

Table 3 shows that Lewis' mispronunciations, more than doubled across the duration of the project and that his use of substitution of words more than tripled. However, the table does not show the level of passages attained by Lewis. In the pre-test Lewis was able to read only the first two passages. In the post-test Lewis read four passages, with each passage increasing in length and complexity. The mispronunciations and substitutions occurred mainly in passages three and four in the post-test results and occurred mostly on larger, more difficult words. This table shows that Lewis' omissions more than halved. This would indicate an improvement in Lewis' fluency and attention to text. It is likely that the substantial decrease in omissions (and thus increase in fluency) contributed to the gains made in the comprehension aspect of this test.

| Mispronunciation | Substitution | Refusal | Addition | Omission | Reversal | Total | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-intervention | 2 | 7% | 3 | 11% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 23 | 82% | 0 | 0% | 28 | 100% |

| Post-intervention | 5 | 18% | 10 | 37% | 1 | 4% | 0 | 0% | 11 | 41% | 0 | 0% | 27 | 100% |

Table 3 | Frequency of errors made on the Neale Analysis of Reading Ability, 3 rd edition (1999)

Observations of key strategies

Accessing prior knowledge and past experiences

At the beginning of the intervention Lewis had difficulty discussing in depth his prior knowledge and past experiences related to specific topics even with picture stimuli. With the ongoing use of strategies to enhance his abilities, Lewis' skills developed and with verbal prompting he became increasingly able to access prior knowledge and past experiences and discuss these in depth. When the reading series (Wilson, 1980-1997) was introduced Lewis was able to access prior knowledge and past experiences related to the title/topic of the text but experienced difficulty making links between his personal experiences and the text. Strategies were employed to make links that would utilise prior knowledge to aid understanding of the text yet remain focussed upon the details of the text rather than the prior knowledge and past experiences. Towards the end of the intervention Lewis' ability to access prior knowledge and utilise it in the construction of meaning from text had improved. The following is a transcript taken from observations from Week 13 of the intervention which highlights Lewis' ability to access prior knowledge and past experiences related to the title of a text.

- Text Genre: Narrative

- Text title: "I Bought My Lunch Today" (adapted from Lorraine Wilson's original text, 1986 and updated text, 1997 ) ("M" denotes first author; "L" denotes Lewis)

- M Please read the title for me

- L "I bought my lunch today"

- M (removes text) OK, we need to think about everything we know about buying our lunch. What do you know about buying your lunch?

- L Well I go and get a hamburger and everything.

- M Mmmm a hamburger. Where do you go to get a hamburger?

- L In the canteen shop at the Uni.

- M Yes, you get hamburgers at the Uni canteen. How do you get there?

- L I walk

- M Yes. Who do you go with?

- L Myself

- M Just by yourself. Who else could you go with?

- L Well I go by myself, but I could go with a group of my friends up to the canteen shop.

- M Yes you could go with your friends. Who is a friend of yours from Uni?

- L Oh at Uni I have Trent, Nathan and Oscar. 2

- M Yes, they're all friends and they could go with you to buy their lunch too. What would you buy?

- L Well Mum made my lunch today but for afternoon tea I'm going to have an ice-cream.

- M Oh an ice-cream. Mums do make lunch sometimes don't they? But if Mum didn't make your lunch today, and you could go to the shop to buy your lunch, what would you buy?

- L A hamburger and chips

(Lewis laughs and smiles as the text is handed to him. He is eager to begin reading)

Prediction

Strategies to aid in the prediction of what the text might be about based upon the title or topic of a text were introduced with the improvement of Lewis' use of prior knowledge. Links between the topic and title of the text and past experiences were established to aid in prediction activities. The predictions were listed on the left side of a chart. The text was then read and discussed. Actual details from the text were then listed on the right side of the same chart and compared to the earlier predictions (see Table 4). These details together with sequence words were used to aid in the sequencing and retelling of the text. Lewis' ability to predict the context of the text based upon his prior knowledge and personal experiences developed across the intervention and aided his ability to discuss the text following the reading.

The following is a transcript taken from observations from Week 11 of the intervention which highlights Lewis' ability to make predictions about a text based upon his prior knowledge and personal experiences.

- Text Genre: Narrative

- Text title: "The Lake" (This text is one paragraph in length and was written by the first author for the purpose of the intervention). ("M" denotes first author; "L" denotes Lewis)

- M Please read me the title

- L "The Lake"

- M "The Lake". Without reading the story, we're going to turn it over. (M turns the story over so that it cannot be read). We know it's called "The Lake", so what do you think it might be about? I'm going to write up all the things you think this story might be about. What do you think it might be about?

- L About the holidays I think

- M You think it might happen on the holidays? (M writes "Holidays" in the left column) What else? What might you do at the lake?

- L Catch a fish

- M Yes, you could go fishing (writes "Fishing" in the left column) What else? What things would you have if you were fishing?

- L A picnic

- M Yes, you could have a picnic

- L A fishing picnic (L laughs at this as M writes "picnic" in the left column)

- M Where would you fish from?

- L Um, I'd need a BBQ for the fish

- M So you'd need a BBQ to cook the fish?

- L Yes, that's right (M writes "BBQ" in the left column)

- M OK. How do you catch the fish?

- L In the lake

- M What with?

- L A fishing rod (M writes this in the left column)

- M So there could be a fishing rod in this story. Where would you be? On the land, in a boat, on a jetty?

- L In a boat (M writes "boat" in the left column)…

- M Anything else that you think might happen in the story? Who do you go fishing with?

- L Dad (M writes this in the left column)

- M You might go fishing with Dad. We're not sure what might be in this story yet are we? We've talked about things that we've done in the past, and written our guesses about what might be in the story on the board. Let's read the story and see if we guessed what it might be about.

The text was read and the key events in the text were listed in the right column and compared to the predictions made prior to the reading. The predictions that were found in the text were ticked. The text elements that matched the ticked predictions were underlined. Table 4 provides a reconstruction of the prediction chart.

| Our Guess | The Story |

|---|---|

| • Holidays √ • Fishing √ • Picnic • BBQ to cook fish • Fishing rod • Boat • Near a park • Dad √ | · Drove to the lake · Went with Dad · Holidays · Fishing in a boat · Middle of the lake · The biggest fish are in the |

Table 4 | Prediction Chart

Re-telling

At the beginning of the intervention Lewis was unable to recall details of the text used in pre and post testing. He was unable to spontaneously re-tell the text. His re-telling was in the form of single word answers to verbal prompting, the answers being located from the text with the utilisation of re-reading to locate specific information. Lewis was not confident and became agitated when he could not recall details of the text he had just read. The following is an excerpt of a transcript taken from observations of Lewis' retelling in the pre-testing phase.

- Name of participant: Lewis Phase A - Pre-testing phase

- Text Genre: Narrative

- Text title: "My Dog's in Trouble" written by Lorraine Wilson (1987).

- (Transcript begins at completion of reading by participant) ("M" denotes first author; "L" denotes Lewis)

- (Lewis is sitting back comfortably in his chair. His arms are held loosely in his lap and his legs are apart.)

- M Now what I want you to do is tell me that same story in your own words.

- (Lewis' hands tense and intertwine).

- L Own words

- (His head quickly drops and he wipes his nose with his hand while looking down at the floor.)

- M Yes - now all you have to do is - you've read the story - now I just want you to tell me the story.

- (Lewis' hand drops back to his lap. He continues to look down.)

- L Mmm - Oh God

- (His left hand moves up to his face and covers it.)

- M OK What if I give you a few little bits of help here? OK?

- L OK

- (He now takes his hand from his face and looks up and across at M)

- M What was the story about?

- L (mumbles to himself, then whispers, "about") My dog's in trouble.

- (He lifts his head immediately. His eyebrows are raised and he nods his head with clear satisfaction and allows a small smile).

The transcript continues with the first author asking Lewis direct questions about the text and Lewis answering by reading his responses directly from the text.

With the gradual and progressive use of the other strategies within the intervention phase (including strategies employed to enhance fluency and promote task persistence and motivation as well as the use of suitable texts) Lewis' confidence in his own abilities grew. He gradually required less specific verbal prompting to recall details of text. His ability to recall details and re-tell a text progressively improved. Towards the completion of the intervention Lewis was confident in his ability to recall details of a text. He was able to recall most of the details of the text and re-tell mostly in the sequence in which the events occurred with some prompting that was mostly non text-specific. When prompting was required he was able to respond appropriately to the questions and there was a clear indication that he was effectively constructing meaning from the text. With continued instruction it is expected that Lewis would be able to retell longer texts and that his retelling would extend from short answers and would occur with less prompting.

The following transcript is taken from Week 14 at the conclusion of the intervention. The text is the same as in the pre-testing phase but following the reading, the text is removed.

- Name of participant: Lewis Phase C- Post-testing phase

- Text Genre: Narrative

- Text title: "My Dog's in Trouble" written by Lorraine Wilson (1987).

- (The transcript begins at the completion of reading by the participant, the text has been removed).

- (M" denotes first author; "L" denotes Lewis)

- M Tell me about the story. Everything you can remember

- L Well it's all about his father and his dog. Mmm (L screws up his face and taps his hands on the desk) The dog does stupid things on that day. (L sits back and looks at M for a response)

- M Yes, she does do stupid things. What does she do?

- L Oh, like the washing on the line (L is animated, his head is up and he is smiling broadly as he answers)

- M Excellent, keep going, this is great!

- L OK (smiling) dressing gown, rips everything! (looks at M)

- M Yes, and then what did she do?

- L Oh yes, and he asks his father if he can take it home

- M That's right! Because what did the dog do? (L looks confused) What was the naughty thing that the dog did at the neighbour's house?

- L Um (Looks down and bites his bottom lip)

- M Something very naughty

- L (looks up smiling) Well it's about the chooks!

- M Yes, it was about the chooks. What did she do to the chooks?

- L I don't know. I think it was barking - ruff, ruff, ruff.

- M Well it was something worse than barking.

- (M produces the text and puts it in front of L. M points to the part about the chooks)

- L (glances briefly at text) Oh, kill!

- M Yes she killed them. Gee you did well. You remembered so much of the story. Excellent!

- (L is clearly proud, laughing, smiling. He is so thrilled with his achievements that he begins whistling!)

Conclusion

The preliminary findings appear to indicate that the programme of specific teaching and learning reading comprehension strategies used in this project was beneficial in enhancing Lewis' reading comprehension. Similar positive results are being found among the other participants. It is hoped that as the results are analysed and the findings documented, a more complete understanding of effective pedagogies and strategies for the teaching and learning of young adults with Down syndrome will ensue. It is also hoped that the benefits from this project will lead to improved practice in other settings and further studies of the teaching practice of adults with intellectual disability.

Correspondence:

Michelle Morgan • The School of Education, The University of Queensland, St. Lucia, Queensland, 4072 • Tel: 07 3365 7383 • E-mail: s4015821@student.uq.edu.au

References

- Bird, G., Beadman, J. & Buckley, S. (2001). Reading and Writing for Children with Down Syndrome (5-11 years). Portsmouth, UK: The Down Syndrome Education Trust. [Open Access Full Text]

- Bochner, S., Outhred, L. & Pieterse, M. (2001). A study of functional literacy skills in young adults with Down syndrome. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 48(1), 67-90.

- Broadley, I. & MacDonald, J. (1993). Teaching short term memory skills to children with Down's syndrome. Down's Syndrome Research and Practice, 1, 56-62. [Open Access Full Text]

- Burt, C. & The Scottish Council for Research in Education. (1976). The Burt Word Reading Test, 1974 Revision. London: Hodder and Stoughton Ltd.

- Chard, D.J. & Kame'enui, E.J. (2000). Struggling first grade readers: The frequency and progress of their reading. Journal of Special Education, 34(1), 28-38.

- Doyle, C.S. (1999). The use of graphic organisers to improve comprehension of learning disabled students in Social Studies. Unpublished MA Dissertation, Kean University, New Jersey.

- Dunn, L.M. & Dunn, L.M. (1997). Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test - Third Edition, Form IIIA. Circle Pines, NN: American Guidance Service.

- Elliot, J. (1991). Action Research for Educational Change. Buckingham & Philadelphia: Open University Press.

- Farrell, M. (1996). Continuing literacy development. In B. Stratford & P. Gunn (Eds.), New Approaches to Down Syndrome (pp. 280-299). London: Cassell.

- Farrell, M. & Elkins, J. (1994/5). Literacy for All? The case of Down syndrome. Journal of Reading, 38(4), 270-280.

- Fournier, D.N.E. & Graves, M.F. (2002). Scaffolding adolescents' comprehension of short stories: this article describes an approach to assisting seventh-grade students' comprehension of individual texts with a Scaffolded Reading Experience or SRE. Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy, 46(1), 30-40.

- Fowler, A.E., Doherty, B.J. & Boynton, L. (1995). The basis of reading skill in young adults with Down syndrome. In L. Nadel & D. Rosenthal (Eds.), Down Syndrome: Living and Learning in the Community (pp. 182-196). New York: Wiley-Liss.

- Gardill, C.M. & Jitendra, A.K. (1999). Advanced story map instruction: Effects on the reading comprehension of students with learning disabilities. Journal of Special Education, 33(1), 2-17.

- Gerston, R. (2001). Teaching reading comprehension strategies to students with learning disabilities: A review of research. Review of Educational Research, 71(2), 279-321.

- Hopkins, D. (2002). A teacher's guide to classroom research - 3 rd edition, Buckingham & Philadelphia: Open University Press.

- LANDA (Literacy And Numeracy Diagnostic Assessment) Project. (1990). Folio of Literacy Assessment Devices Part 1: Influences (Trial Edition). Queensland: Division of Special Services, Department of Education Queensland, Australia.

- Levy, S. & Chard, D. (2001). Research on reading instruction for students with emotional and behavioural disorders. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 48(4), 429-444.

- Moni, K.B. & Jobling, A. (2000). LATCH-ON: A programme to develop literacy in young adults with Down syndrome. Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy, 44(1), 40-49.

- Moni, K. & Jobling, A. (2001). Reading related literacy learning of young adults with Down syndrome: findings from a three year teaching and research programme. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 48(4), 377-394.

- Moody, S., Vaughn, S., Hughes, M. & Fischer, M. (2000). Reading instruction in the resource room: Set up for failure. Exceptional Children, 66, 305-316.

- Neale, M.D. (1999). Neale Analysis of Reading Ability - 3 rd edition. Australia: Australian Council for Educational Research.

- Nguyen Bui, Y. (2002). Using story grammar instruction and picture books to increase reading comprehension. Academic Exchange Quarterly, 6(2), 127-133.

- Polloway, E.A., Patton, J.R. & Serna, L. (2001). Strategies for Teaching Learners with Special Needs (7 th ed.), Columbus Ohio: Merrill Prentice Hall.

- Pressley, M., Wharton-McDonald, R., Hampston, J.M. & Echevarria, D. (1998). A survey of the instructional practices of grade five teachers nominated as effective in promoting literacy. Scientific Studies of Reading, 1, 145-160.

- Torgesen, J.K., Wagner, R.K., Rashotte, C.A., Alexander, A.W. & Conway, T. (1997). Preventive and remedial interventions for children with severe reading disabilities. Learning Disabilities: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 8(1), 51-61.

- Tunmer, W.E. & Hoover, W.A. (1992). Cognitive and linguistic factors in learning to read. In P.B. Gough, L.C. Ehri & R. Treiman (Eds.), Reading Acquisition (pp. 175-214). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- van Kraayenoord, C.E. (Ed.). (1992). A survey of adult literacy provision for people with intellectual disabilities: Volumes 1, 2, and 3. Report to the International Literacy Year Secretariat. Brisbane, QLD: Schonell Special Education Research Centre, Queensland Division of Intellectual Disability Services and Division of Adult Education, Access and Equity.

- van Kraayenoord, C.E., Elkins, J., Palmer, C. & Rickards, F.W. (2001). Literacy for all: Findings from an Australian study. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 48(4), 445-456.

- van Kraayenoord, C.E., Moni, K.B., Jobling, A. & Ziebarth, K. (2001). Broadening approaches to literacy education for young adults with Down syndrome. In M. Cuskelly, A. Jobling & S. Buckley (Eds.), Down Syndrome: Into the New Millennium. London: Whurr.

- Vaughn, S., Moody, S.W. & Schumm, J.S. (1998). Broken promises: Reading instruction in the resource room. Exceptional Children, 64(2), 211-225.

- Waddington, N.J. (1988). Waddington Diagnostic Reading and Spelling Tests: A Book of Tests and Diagnostic Procedures for Children with Learning Difficulties. South Australia: Waddington Educational Resources.

- Wilson, L. (1980 - 1997). The Best of City Kids/Country Kids Reading Series, Melbourne, Australia: Thomas Nelson.

- Wilson, L. (1987). My Dog's in Trouble. Melbourne, Australia: Thomas Nelson.

- Worthing, B. & Laster, B. (2002). Strategy access rods: A hands-on approach. (teaching ideas). The Reading Teacher, 56(2), 122-124.

1 pseudonym

2 pseudonyms