The voice of the child with Down syndrome

An exciting multi-agency project to create a future for children with Down syndrome where they can more effectively express their opinions. This work recognises the need to remove barriers and push boundaries associated with the reduced ability to verbalise and was planned to give every child with Down syndrome in mainstream schooling in Buckinghamshire the chance to express themselves in an alternative way and to chart visually their own judgement of progress. It explores success in enabling a child to be able to contribute in a personally meaningful and accurate way to the annual review process and beyond, using complementary professional expertise.

Down Syndrome Research and Practice (2008)

"We are used to people saying we cannot communicate, but of course they are wrong. In fact we have powerful and effective ways of communicating and we usually have many ways to let you know what it is we have in mind. Yes, we have communication difficulties, and some of those are linked with our impairments. But by far the greater part of our difficulty is caused by 'speaking' people not having the experience, time or commitment to try to understand us or to include us in everyday life."

Quote from a disabled child with communication impairment [1].

Since the 1990s, national and international policies have placed a greater emphasis on improving services for people and children with disabilities and in involving them in decisions about their lives. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (Articles 12 and 13 [2] ) directed attention to the 'voice of the child' and a need for an appropriate means of communication. Acknowledgment was given that children are capable of forming views, have a right to receive and make known information, to express an opinion and to have that opinion taken into account in any matters affecting them. A range of studies have demonstrated that children with disabilities and communication difficulties are often overlooked in planning and decision making processes that directly affect them [3] . Primarily, their opinions continue to be expressed by those adults who are close to them such as their family and school support staff, although their perspectives and experiences can differ from those of the children themselves [4] and therefore are somewhat second hand. Children with Down syndrome are at risk of having their abilities underestimated in this area and their views ineffectively consulted, as they have communication difficulties as well as learning difficulties [5] . The challenge has been to create an effective and appropriate means of communication which can be used by a child with Down syndrome to express genuine first hand opinions, in spite of his or her disabilities and communication difficulties.

Since the 1990s, national and international policies have placed a greater emphasis on improving services for people and children with disabilities and in involving them in decisions about their lives. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (Articles 12 and 13 [2] ) directed attention to the 'voice of the child' and a need for an appropriate means of communication. Acknowledgment was given that children are capable of forming views, have a right to receive and make known information, to express an opinion and to have that opinion taken into account in any matters affecting them. A range of studies have demonstrated that children with disabilities and communication difficulties are often overlooked in planning and decision making processes that directly affect them [3] . Primarily, their opinions continue to be expressed by those adults who are close to them such as their family and school support staff, although their perspectives and experiences can differ from those of the children themselves [4] and therefore are somewhat second hand. Children with Down syndrome are at risk of having their abilities underestimated in this area and their views ineffectively consulted, as they have communication difficulties as well as learning difficulties [5] . The challenge has been to create an effective and appropriate means of communication which can be used by a child with Down syndrome to express genuine first hand opinions, in spite of his or her disabilities and communication difficulties.

Within Buckinghamshire, specialist services are available for children with Down syndrome who attend mainstream schools. The Buckinghamshire County Council Specialist Teaching Service Down Syndrome Support Team provide holistic support and Symbol UK provide speech and language therapy. Following the updated guidance in Buckinghamshire on the annual review process for a child's Statement of Special Educational Needs, attempts have been made to ensure that children are given greater involvement in the process. In the period from September 2005 to September 2006 an audit of 48 children with Down syndrome in mainstream Primary and Secondary schools in Buckinghamshire showed that only 8 were given an opportunity to contribute to their Annual Review process. 1 of these 8 contributed via the appendix E iii format of County guidance, 1 via SEN Service format and 6 were made using individual school's own comment sheets. 2 of the 8 were contributed in third person text and 5 were in adult staff's writing or typing. 3 incorporated pupils' writing and 1 used symbols to facilitate their involvement.

It has been identified that in order to enable children's ability to contribute to decision making processes, there is a need for greater training of staff, peers and families linked to children with communication difficulties [6] . Furthermore, a focus is necessary on providing the appropriate tools to enable children to participate and express themselves [7, 8] . Booth and Booth [9] suggest that 'researchers should attend more to their deficiencies than to the limitations of their informants' (see p. 67). Additionally the SEN Code of Practice [10] and the DfES publication 'Removing Barriers to Achievement' [11] both state that all children, regardless of the severity of their disability, will have an opinion and should be given the tools to express this.

In view of all of this a joint project was initiated with the Down Syndrome Support and Symbol UK services working in professional partnership in order to identify an appropriate tool. This was firstly trialled in order to permit children with Down syndrome to contribute to the best of their potential to the annual review process and needed to consider the profile of strengths and needs with which these children present:

- auditory memory difficulties

- increased likelihood of hearing loss

- strengths in social interaction

- a preference for learning from visual rather than auditory information

- difficulties developing expressive language but strengths in the area of receptive language

- difficulties with speech intelligibility related to low muscle tone and impairment of phonological loop

- difficulties with fine motor skills which may affect ability to record information

- likelihood of limited concentration span

- likelihood of responding well to clear structure and instructions.

The specialist teams are able to offer advice and support based around this particular learning profile or phenotype. This revolves around developing communication and interaction, improving speech clarity, differentiating the curriculum and promoting inclusion. The specialist teams each provide complementary professional perspectives which promote a multi-disciplinary approach to working with children with Down syndrome including liaison with families, school staff and other involved professionals such as occupational therapists and hearing support services.

Several existing tools used for consulting people with disabilities were studied, including Kirkbrides's Toolkit [12] and questionnaires but the tool 'Talking Mats' was selected to be explored in depth.

Talking Mats is a visual framework that uses picture symbols to help people with a communication difficulty. Joan Murphy, a Specialist Speech and Language Therapist working with the AAC Research Unit at the University of Stirling first described the framework in 1998 working with adults with cerebral palsy [13] . Talking Mats is an interactive resource that uses 3 sets of picture symbols - topics, options and a visual scale - and a textured mat, such as a thin door mat from Ikea, on which to display them. Symbols, such as those produced by Boardmaker, are always complemented with text. On meeting and being formally trained by Joan Murphy in the proper and sensitive use of Talking Mats, it became clear that the tool looked workable, appropriate and had obvious benefits:

- It uses a visual approach to communication which complements the typical learning style of individuals with Down syndrome;

- It is physically simple to manipulate;

- It is low tech, low cost (the mat cost 59p) and a very simple and neat resource;

- It was person-focused and led;

- It allows for a range of opinions to be expressed along a continuum rather than being confined to the language that another person suggests.

Talking Mats also meets the criteria outlined by Rabiee et al. [14] regarding the use of a tool to consult children with communication difficulties: that it should be flexible and adaptable to different ages, needs and abilities.

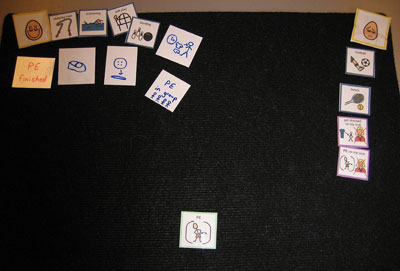

Figure 1 | Talking Mat used in mainstream Primary School; topic - school.

Once the topic for consultation is chosen (e.g. school), it is placed at the bottom mid-line of the mat then the participant is given options one at a time and asked about how they feel about them. When trialling the options were chosen by staff and parents and varied for each child but included some of the following:

- counting

- reading

- lunchtime

- talking to friends

- PE

- assembly

- using the computer

- using the toilet

- wearing glasses

- writing

- lining up and waiting for a turn

- stickers

- sports day

- presentation of work

- chair (particularly if the child had a special chair as recommended by an Occupational Therapist)

- using Numicon (a visual multi-sensory approach to arithmetic)

- using a Language Master (a unique audio-visual aid which helps children develop their language and literacy skills).

Figure 2 | Sub-mat; topic - reading.

Using Talking Mats promoted concentration, interaction, enjoyment and independence when children were consulted on their preferences, opinions and wishes. The children had time and space to consider and express their views by placing the symbols on the mat in a position under a 2 or 3 point visual scale which went from 'happy' to 'unsure' to 'sad'. Makaton signing was used to aid the child in understanding the relevance of positioning each option. There was a degree of experimentation with scales running from positive to negative or negative to positive responses and also the use of 'like' to 'don't like' replacing 'happy' to 'sad'. It formed a wonderfully neat and concise way of presenting information in manageable chunks and attempting to tap that which comes from the heart of the child in a way which can be easily recorded.

The mats were confirmed by each child at the end and then photographed using a digital camera and printed instantly so that the child could take a copy home and create a sense of true ownership. The photograph could then be included in the reporting used in the annual review or indeed should it be possible and appropriate for a child to attend the annual review meeting, then the photograph could be brought in by the child in order to use it as a visual prompt.

The neatness of the tool is one of its obvious assets but the beauty of the tool becomes even more apparent when it becomes appropriate to continue to do a sub-mat using a symbol which has been placed in an unexpected position on the mat, such as in the sad section. Moving the option to the bottom mid-line of the mat turns it into a new topic, which allows issues to be explored in deeper layers (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 3 | Talking Mat used in mainstream Secondary School.

Blank symbols can be used in order to spontaneously respond to situations when the child wanted to move the communication in a certain way (Figure 2). For example, one child with Down syndrome who very quickly picked up on the informal and non-threatening format responded with great joy and obvious signs of enjoyment in his newly found empowerment. However, this child chose a 'sad' position for a reading symbol (Figure 1) and as reading was one of his strengths, this was a surprise to the staff interviewing and observing.

The reading symbol was then placed at the bottom mid-line so as to become the topic and further option symbols were used, including adult drawn symbols so that it was possible for the child to elaborate more deeply (Figure 2).

This child was able to show that he was happy about the reading and worksheets at school, that he enjoyed working in a group on his reading, that he was happy to be helped with his reading, that he liked Mr Men books, happy books and funny books and also reading at home but that he was not keen on reading at school, working alone or questions about books. Further analysis suggested that the child had got to a stage in the Oxford Reading Tree scheme where the scheme did not seem to be meeting his needs and decisions had been made by adults for him to go back over the complete last stage of books he had read in order to 'work on comprehension'. Investigation using Talking Mats enabled him to show his displeasure at this move and a change of reading material was introduced with the intention of carrying out a subsequent mat afterwards in order to try to ascertain the child's opinion again. This child had a mainstream school placement and his behaviour was seriously challenging staff. He had limited speech but important things to say about his own education and choices.

Figure 4 | Summary mat.

Some young people have been able to indicate themselves that there are areas that they want to explore more fully. A secondary-aged girl with Down syndrome selected her learning support assistant (LSA) as a topic for further discussion on a sub-mat. She indicated through placement of the symbols that she liked working with her LSA and enjoyed tackling some lessons and tasks on her own but felt unhappy when she had less help with some things (Figure 3). She supplemented this with speech to clarify her responses. We conducted a final 'summary' mat for her to tell us the topics with which she would like more help (Figure 4).

This opportunity further empowers children and young people to be able to express their own concerns rather than simply depend on those identified by professionals and carers. The unexpected outcomes of the Talking Mats in many ways proved to be most interesting and helpful in analysing practice which might well have been assumed was going as well as could be expected, when in reality the child was somewhat unhappy and unable to verbalise what was causing this. The deterioration of behaviour is so often a result of such frustration.

However, there have been instances where misinterpretation has occurred both on the child's and the adult's side. One child identified the 'sad' symbol used on the mat (which featured a simple face with a bald head) as her head teacher! When anything she associated with the head teacher (such as assembly) was discussed, the child enthusiastically placed the topic under the character. Until we realised the connection that she had made, we had assumed that she felt unhappy about a number of issues within school. It is prudent to ensure that the child has a clear understanding of the symbols used before commencing the interview.

Figure 5 | Talking Mat used in mainstream Secondary School.

It is also clear that background information from as many people as possible should be collected before using Talking Mats. A young girl with Down syndrome indicated on her mat that she was 'sad' about PE - this was explored in depth in a sub-mat (Figure 5), but the professionals were unable to find a clear reason as to why she felt this way. However, another member of staff later told us that she had been told off in PE earlier that week which explained her response more accurately. Talking Mats will offer a snap shot of an individual's opinions at a certain time and it can be useful to repeat the exercise at a later time to confirm responses.

Children with Down syndrome have many ways of letting those who engage and work with them know what they have in mind. By working together in partnership, Symbol UK and the Buckinghamshire County Council Down Syndrome Support Service have harnessed their complementing expertise and enabled a rigorous tool to be introduced which gets far closer to enabling effective consultation and giving children the opportunity to express their opinions themselves. The project was primarily initiated in order to give the chance for children with Down syndrome to contribute to the annual review process. Yet there is great potential for using Talking Mats in a wide range of areas such as involvement in future planning, facilitating counselling for people with learning and communication difficulties and conflict resolution. In response to government policy and increased recognition of the rights of people with learning difficulties, it is necessary to raise expectations of multi-agency professionals working with individuals including educational staff, social services and health care, so that a child, young person or an adult with learning difficulties will be consulted on major issues. More important, however, is that the individual with a learning difficulty is empowered to believe and expect that they will be fully involved and influential in issues about their lives. An expectation of consultation within schools is created. The scope which Talking Mats has for overriding communication difficulties and truly facilitating the voice of the child with Down syndrome - even if that child has no 'voice' - is immense and exciting.

References

- SCOPE. The Good Practice Guide, for Support Workers and Personal Assistants Working with Disabled People with Communication Impairments. Scope; 2002.

- United Nations. Convention on the Rights of the Child. New York: United Nations; 1989.

- Morris J. Space for us: Finding out what disabled children and young people think about their placements. London Borough of Newham; 1999.

- Mitchell W, Sloper R. Quality in services for disabled children and their families: What can theory, policy and research on children's and parents' views tell us? Children and Society. 2001:15; 237-252.

- Morris J. Including all children: Finding out about the experiences of children with communication and/or cognitive impairments. Children and Society. 2003:17; 337-348.

- Clark M, McConachie H, Price K, Wood P. Views of young people using augmentative and alternative communication systems. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders. 2001:36; 107-115.

- Department of Health (1991). The Children Act Guidance and Regulations: Volume 6 Children with Disabilities. London: Department of Health; 2001.

- Department of Health. Getting the Right Start: The National Service Framework for Children, Young People and Maternity Services - Emerging Findings. London: Department of Health; 2003.

- Booth T, Booth W. Sounds of silence: narrative research with inarticulate subjects. Disability and Society. 1996:11; 55-69.

- Department for Education and Skills. Special Education Needs: Code of Practice. London: Department for Education and Skills; 2001.

- Department for Education and Skills. Removing Barriers to Achievement: The Government's Strategy for SEN. London: Department for Education and Skills; 2004.

- Kirkbride L. I'll go first: the planning and review toolkit for use with children with disabilities. London: The Children's Society; 1999.

- Murphy J. Talking Mats: Speech and language research in practice. Speech and Language Therapy in Practice. 1998: Autumn; 11-14.

- Rabiee P, Sloper P, Beresford B. Doing research with children and young people who do not use speech for communication. Children and Society. 2005:19(5); 385-96.

Received: 18 September 2007; Accepted 21 January 2008 ; Published online: 8 July 2008